Felix Amerbacher

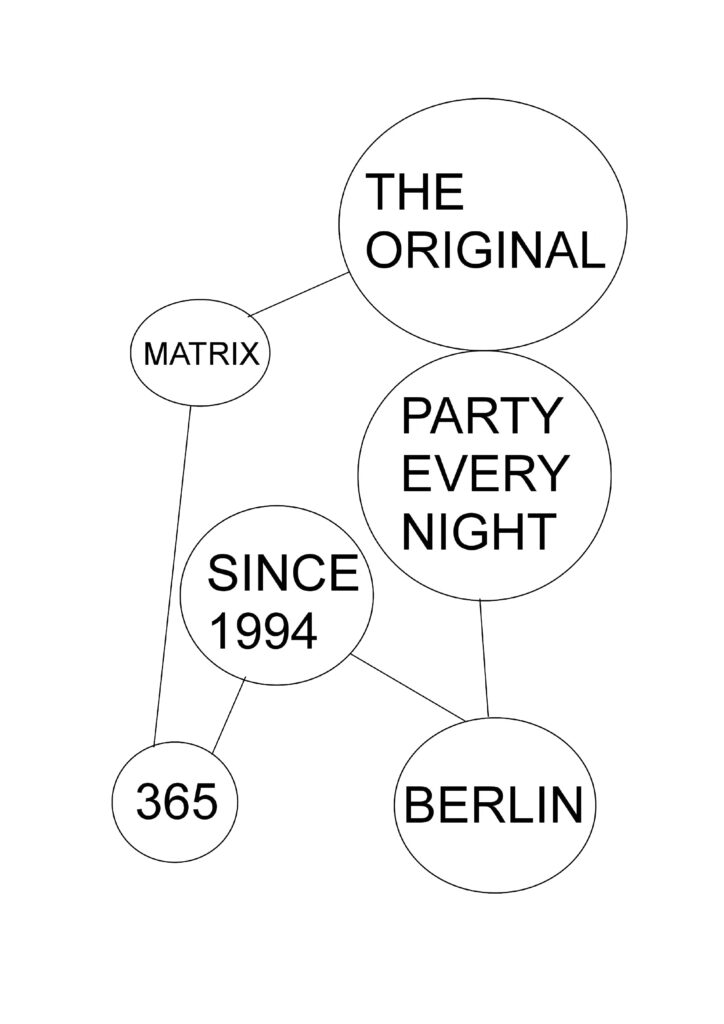

Die Matrix, 2020

Seven replicas of a poster (each 59,4 x 84,1 cm) installed on the walls of a vacant accommodation

Gibt’s noch Gästeliste?

The toothless smile of an old building returns your examining gaze. It repeats its straightforward message seven times, as if to cast a spell upon us:

PARTY

EVERY

NIGHT

We are facing a poster that advertises a blunt temple of alcohol and popular music. It has been repeatedly posted into an empty Berlin Altbau flat. Of course, we all know where we would rather go (if we just could). The venue advertised here offers a safe haven for non-subcultural partygoers, lost students and suburban kids. A glance at their social media profiles activates a world of classism. I feel pity and vicarious embarrassment for those poor souls that are being lured into the literal Matrix.

The undemanding craftsmanship shown here continues a line of Felix Ammerbachers work that wavers between Arte Povera and—nearly—untouched found objects. No doubt, the artist also has an open flank to outsider art. Like a stubborn descendant of the lacerated poster artists of Europe’s neo-avantgarde after WWII, he plays a daring game of push and pull. Our artistic taste buds are irritated by his reflections on the naturalised exclusions connected with contemporary arts and its spheres of display. Subsequently, the tiled stove of the living room cuts the initial phrase down to:

PART

EVER

NIGH

I still have pleasant shivers when I imagine the whining noise of a metal drill finding its way through the lock cylinder of this very flat. Instead of a well negotiated interim use of real estate in the name of philanthrocapitalism, Felix Amerbacher opted for immediate access. The temporal appropriation of scarce resources gone to waste by speculation in capitalist society is an ubiquitous, thus invisible part of the exhibition. The transgression of property rights disturbes the borders between artistic practice and the realm of life itself.

You can’t imagine—as all the city’s clubs and bars have been closed for months—the explosion of pent-up energy during the preview night. Perhaps, it was a bad idea to let all of this happen in the midst of a global pandemic, but wouldn’t you have liked to join as well? Don’t be scared, you don’t have to feel embarrassed about not being invited. In fact, the show never opened. Nobody smoked next to an open window. There was never a queue in front of the bathroom.

I’m judging this show on the same databases as you. A set of pictures that could—if we didn’t know better—be taken to advertise a flat on offer. Just with the little glitch of carrying Berlin city’s very promises from public into private space. The bad breath of authenticity is unpleasantly noticeable. Formulated as tasting notes, we start with wet wood, cold cigarette smoke and end up with a broad aftertaste of cheap household cleaners and stale wall paint.

Berlin.365

Plato’s cave literally seems to have come to life in Berlin’s S-Bahn Ring. Anything outside the tracks of the circular railway is deemed an inhabitable territory for an individualistic urban dweller. Please tell your fellow prisoners to stay calm and enjoy the shadowplays of the artscape. These days, it’s quite hard to tell who is on which pill, so any questions regarding The Matrix remain vague. Berlin’s housing crisis is the biggest comedown of the last hundred years.

Just now the lid of the socioeconomic pressure cooker was lifted. The ruling of the city’s

unique rent cap as unconstitutional leaves numerous Berliners in debt, and more important: anger. The campaign ›Deutsche Wohnen & Co Enteignen‹ is their last hope, campaigning for a far more apt intervention, the expropriation of thousands of units now in the hands of real estate investment firms.

The Original

Since 1994

»Pardon 1988«. Ever since, contemporary Berlin seems to be cannibalising its mythical past of the 1990s, where the gods were still alive and space was available in abundance. As an actual Berliner, Amerbacher grew up where our holidays and business trips took us at the same time. Who else is supposed to do the job of throwing the city’s very promises into its contradictory opposite sphere: the private space?

Lars Karl Becker

PS I am delighted to inform you that this very flat was silently squatted and became someone’s new home by the time this text is published.